Waterbury families get helping hand for private school tuition

by Marc E. Fitch

Connecticut Inside Investigator

May 4, 2022

Juliana is 11 years old and one of nine children, nearly all of whom have attended the Children’s Community School in Waterbury, a private, non-profit school that began in the 1960s when some Catholic nuns began to offer after-school tutoring for city students.

Juliana doesn’t know yet what she wants to do later in life, but for now math is her favorite subject. As CCS only goes through middle school, in a few years she will have to choose a high school to attend in Waterbury, which might seem like a daunting decision for a young girl who has spent 8 years – including Pre-kindergarten – at this small, unassuming school in a beleaguered part of the city.

Until last year, Juliana and her family lived right across the street. While the school’s tuition is roughly $4,200 per year per student, CCS uses scholarships and donations to get the cost for low-income families down to roughly $500 per year.

But for a large family like Juliana’s that could still add up to several thousands of dollars. This year, Juliana’s family has a helping hand in paying the costs.

Juliana is also one of 20 “scholars” whose tuition is being partly funded through the Children’s Educational Opportunity Foundation of Connecticut, a nonprofit organization that uses donations to cover half the cost of a private school tuition up to $2,100 so students in poor-performing school districts can attend a private school of their choice.

CCS, which has a total student population of 169 students, primarily serves low-income families, with 97 percent of its student population are at poverty level or are considered Asset Limited Income Constrained Employed.

“We have a waiting list in almost every grade,” said CCS Principal Katherin Sniffin. “Our kindergarten waiting list is impossibly long because that’s when parents really want to get a good start for their students.”

Sniffin says the opportunity offered by the CEO scholarships is “absolutely a plus.”

“Every year there are some families, not a lot, there are some families who just cannot keep paying,” she said. “So, we do what we can as far as getting some assistance and support, but we don’t take anybody at zero, they have to be invested. That’s one of the things that makes it successful.”

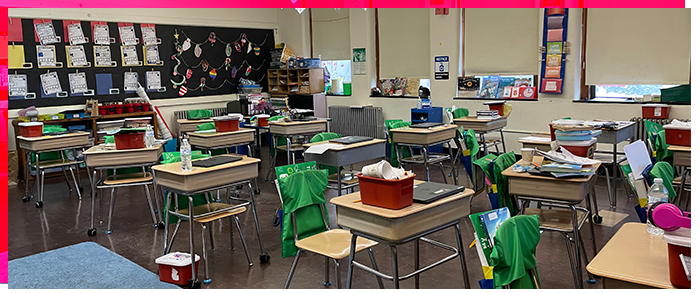

The school building itself is from another era, the playground consisting of space in the parking lot; a little girl from Pre-K is walking through the hall with her teacher to the bathroom, yawning because it’s the middle of nap time. Classes are in session, teachers accompanied by assistants give their lessons in classrooms where the number of students per class is capped at 16, allowing for more personalized attention.

And although the building is old and fairly small, the feeling inside is one of wonder: in an era where municipalities clamor at building the biggest, most fashionable schools they can, CCS offers a glimpse into something more authentic. Most of all, the students appear bright, engaged and happy to be there.

“What helps to make CCS so great is what happens inside these aging classrooms is personalized for our students, the ratio of students to adults is about 8-1, so kids are getting a really great education,” said CCS Executive Director Jeff Martin. “We recognize that if we had all the money in the world and could build the building of our dreams it wouldn’t negate our obligation and responsibility to deliver top notch education. Our mission says nothing about facilities.”

The City of Waterbury is the latest expansion by the CEO Foundation, which also offers scholarships for children in Bridgeport, Hartford, East Hartford and New Haven. When CEO announced they would be opening scholarships for children in Waterbury they were immediately flooded with applications, but there was only so much money to go around.

“We were overwhelmed with applications,” said Carolanne Marquis, executive director of the CEO Foundation. “In a matter of one week we were at full capacity. We went in thinking we were going to offer 42 scholarships, we wound up almost doubling that.”

One of the biggest recipients of CEO’s scholarships is nearby in town at the Yeshiva K’tana School in Waterbury. The Orthodox Jewish school serves roughly 700 children from Waterbury’s Orthodox community who receive both a traditional and religious education on a dual track program.

Tuition at Yeshiva is roughly $7,000 per student and Rabbi Ari Weisenfeld, director of the Connecticut Office of Agudath Israel of America, says that the Orthodox families who send their children to Yeshiva sacrifice a lot in order to give their kids a good education that also conforms with their community’s values.

“In our community we have large families,” Weisenfeld said. “At $7,000 per child, if you have four kids, it’s pretty quickly at $30,000 in tuition costs;” a sacrifice he says Waterbury’s Orthodox families are willing to make for the sake of their children’s education and religious scholarship.

“If you want to know what’s important to somebody, look at what they’re spending money on,” Weisenfeld said. “In the world of politics and the world of public perception, people think of private schools as for the rich parents’ kids in southern CT where its 45k per year and they get private tennis lessons. That’s not the case over here.”

Indeed, it’s not. The school is made up of unassuming buildings left behind by the University of Connecticut that have been adopted by Yeshiva for their school grounds. It’s small, hard to find, and fairly closed off, which the security-conscious administration prefers.

Rabbi Yerachmiel Karr, administrator for Yeshiva K’tana, says their private school status is “not an indication of our feelings toward the local public schools, which do a great job.”

“Every Orthodox community has their own school system because we feel very strongly the need to transmit our values to the next generation,” Karr said. “Things like the CEO foundation, it makes a big difference for parents.”

Expansion into Waterbury

The CEO Foundation began in 1995 with awarding $1,000 scholarships to 100 kids in Bridgeport and has since expanded into five other cities, including, most recently Waterbury. The Foundations focus primarily on struggling school districts with high poverty rates.

Waterbury’s public school district has been a prime example of the education achievement gap, particularly between urban minority students and white students in surrounding suburbs. A 2019 report by the nonprofit organization EdBuild found that Waterbury was the “most isolated school system,” in the country, according to The 74.

Naturally, most arguments come down to school funding. Waterbury, for example, has over 18,000 students and spends $18,800 per child on education, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Just next door, the Town of Cheshire has 4,108 students and spends $20,758 per student. A big part of that funding discrepancy has to do with where the money comes from: Waterbury receives the bulk of its funding, 61 percent, from the state through Connecticut’s Education Grant Sharing program.

Cheshire, on the other hand, receives 74 percent of its funding from the local government funded with property taxes.

And despite having nearly identical teacher to student ratios, Cheshire’s school system was ranked 14th in the state for 2022 by Niche, while Waterbury has consistently been classified an Alliance District school by the state, meaning that it needs help.

Lawmakers have reconfigured the state education cost sharing grant formula several times to prioritize school districts like Waterbury’s, sending an additional $84 million to Alliance Districts when the funding plan is fully phased in by 2028. The new formulation accounts for poverty, wealth and property wealth, among other changes.

But for those parents who may want a different environment for their children, foundations like CEO offer support.

Marquis says the foundation began almost 26 years ago as a way to help those low-income families who were constrained by zip code in school systems that may not be meeting their needs.

“It became obvious that the folks who didn’t have much option as to where their children were educated and how they were educated were the low-income people, particularly those in the inner cities,” Marquis said. “I believe with all my heart that these parents really do know what their kids need.”

Applicants must show that they meet the income restrictions to receive the help, but must also help pay for the costs themselves, a part of CEO’s philosophy that parents must have some skin in the game to ensure their child’s success.

“It’s important because it’s not a handout. It’s important because they have the choice of where they want their child to go, they have to be the ones to apply to us and they have to agree that they will do their part,” Marquis said of CEO scholar parents. “We want the parents involved in this, we want them contributing, we want them involved in the school and they are. They’re very appreciative and very involved.”

The Foundation had 368 scholars for the 2021-22 school year funded through private donations. According to CEO the average family income for those scholars is $33,463 per year, with the families contributing an average of $4,964 toward tuition.

While the Foundation was able to fund 368 students during the last school year, there was a rather lengthy waiting list of 268 students that CEO couldn’t fund this year and legislation that perhaps could have supported CEO’s and other foundations’ efforts appears to have stalled.

A Tax Credit for Donations?

Last year a bill that came before the Finance, Revenue and Bonding Committee would have allowed tax credits for donations to K-12 scholarship foundations. It received ample public support during its public hearing session from a diverse group of backers, ranging from the Heritage Foundation to Black Lives Matter 860. The bill was co-sponsored by a bipartisan group of lawmakers as well.

A similar bill returned this year with another public hearing before the Finance Committee but again did not receive a vote to pass out of committee during a year of budget surpluses and both the governor and legislative leaders offering up child tax credits, expanded property tax credits, an increased Earned Income Tax Credit, and a three-month gasoline tax holiday.

A number of other states already offer tax credits for donations to scholarship foundations for children K-12. Florida, for instance, saw 111,219 students enrolled in 1,870 different schools through scholarship foundations, which doled out $670 million in education aid to families during the 2019-2020 school year.

“I think it would help a lot. We’ve lost so many of the deductions that you can take,” Sniffin said. “When people who have a lot of disposable income choose to support education, it’s going to be a better sell if they can deduct it off their taxes.”

“Tax credits aren’t that available anymore. but it would be a way for donors to choose this and expand what they’re already giving,” Marquis said. “We have donors now who said they would double their donations if they could get a tax credit.”

David G. Bohn, president and CEO of Preferred Utilities Manufacturing Corporation in Danbury and board member of the CEO Foundation, offered written testimony in support of the 2021 bill.

“I assure you that as a member of the business and corporate community of Connecticut, I would strongly encourage my colleagues to invest in the children who receive educational scholarships and expect the benefit of a tax credit would add strong incentive to raising funds for this essential investment in our future,” Bohn wrote.

Challenges Ahead

The education system in Connecticut and across the country received an unforeseen shock in 2020 as the COVID-19 pandemic prompted state governments to close schools to in-person learning. When in-person education resumed in the fall, schools were faced with daunting challenges: trying to keep kids in masks, social distancing, quarantines, staff shortages, hybrid learning schedules, frustrated parents and exhausted educators.

And by many indications, the school shut down exasperated the achievement gap in Connecticut schools, with many low-income or urban students having limited access to online learning tools or electronic devices. The Hartford Courant found upwards of 20 percent of students were not participating in online learning.

Both school administrators and the state government attempted to right the ship. The State of Connecticut made some inroads with help from hedge fund giant Ray Dalio and the Dalio Foundation, who offered free laptops to low-income students, but the effort was hindered by delays in getting the products shipped and distributed.

A 2021 study by the consulting firm McKinsey & Company found the pandemic left majority Black schools “a full 12 months behind those in majority-White schools, widening the preexisting achievement gap between Black and White students by about a third.”

While private and parochial schools in Connecticut faced the same challenges, their smaller size allowed them to maneuver and adjust more quickly than massive public school systems, according to Jeff Martin at CCS. He said it was comparable to trying to turn a cruise liner around as opposed to a canoe.

The pandemic could be a boost for smaller private schools as some parents who may have been on the fence about seeking out an alternative saw this as an opportunity to move their child into a new setting.

“I would certainly imagine that for those families who may have been thinking about school choice or something different prior to the pandemic, naturally the pandemic has given a little impetus for them to look a little more seriously than they did before,” Martin said.

The Cato Institute noted that there was no national data tracking private school enrollment, but their own study found 47 percent of private schools saw enrollment increases, while 26 percent saw declines.

However, the study also found that private and parochial schools appeared to close their doors for good due to the pandemic, the most reasonable estimate being placed at 287 schools nationwide.

The closure and consolidation of private schools, particularly Catholic schools, in Connecticut has been a trend for a number of years, which leaves Marquis and the CEO Foundation scrambling to get their scholars placed in new schools.

“We’ve had some rough few years with closings and COVID didn’t help,” Marquis said. “Some of the economics of it are stressing. I got hit with three closings in New Haven, one in East Hartford and one in West Hartford, where we had 93 scholars. They were all the Catholic schools. That’s where we got involved and helped the parents move to other places.”

However, Marquis notes, the closings and consolidations “have appeared to stabilize.”

The CEO Foundation opened again for scholarship applications for the 2022-2023 school year in March of this year. Within ten days, the Foundation had filled all 368 scholarship slots with an 86 percent retention rate of families returning for help. However, another 100 families were left on the waiting list.

But these small, private schools that cater to low-income families in urban settings are still at risk, operating on shoe-string budgets. The administrators of these schools are quick to note that they’re not in competition with but rather complementary with the public schools, filling in gaps for students who may have different needs.

Principal of the Bridgeport Hope School Hanabeta Deshotel wrote in testimony to the Finance Committee in 2021 that her private, non-parochial school was at risk of closing without the support of the CEO Foundation.

“Please recall that we who speak today are not asking that any funds be diverted from the public school system. Only to make possible our receiving private donations so that we may continue to serve students who need a different school environment,” Deshotel wrote. “The scholarships we receive from the Children’s Educational Opportunity Foundation are a large part of our operating budget. We could not open our doors without it, and many of our families could not afford to send their child to private school without it.”

Reprinted with permission. This article originally appeared on the Connecticut Inside Investigator website.

Marc E. Fitch

Marc worked as an investigative reporter for Yankee Institute and was a 2014 Robert Novak Journalism Fellow. He previously worked in the field of mental health is the author of several books and novels, along with numerous freelance reporting jobs and publications. Marc has a Master of Fine Arts degree from Western Connecticut State University.